The Loss of the "Mataura" - Desolation Island, Tierra del Fuego (1898)

First reports | Survivors' return to Britain | Board of Trade enquiry

First Reports

Source: "Press", Canterbury, NZ, 29 January 1898

WRECK OF THE S.S. MATAURA.

TOTAL LOSS OF THE VESSEL

ARRIVAL OF A BOAT AT SANDY POINT.

REMAINING BOATS BELIEVED TO BE SAFE.

United Press Association—By Electric Telegraph—

Copyright.

Received January 28th, 1.18 p.m.

London, January 27.

The steamer Mataura was totally lost

near the Strait of Magellan. A boatload of fifteen are saved, and probably

the others.

The New Zealand Shipping Company, Limited, received the following cable message from the London office, dated January 27th: — "Telegram received from Monte Video [sic] to-day:— 'Mataura has gone ashore and is a total loss at Sealers Cove, Magellan Strait, 12th January. Captain, three passengers, doctor, and ten of crew landed at Sandy Point; remaining boats probably safe. Have sent additional assistance.'"

PARTICULARS OF THE VESSEL AND CARGO.

The Mataura, which belonged to the New Zealand Shipping Company, sailed from Wellington for London, via Monte Video and Teneriffe [sic], on December 21st. Her cargo consisted of the following:— 16,535 bales wool and skins, 480 casks tallow and pelts, 51 casks casings, 42 pkgs bone, &c., 2830 pkgs cheese, 11 bales raw skins, 45 bales leather basils [cf. basan; sheepskin roughly tanned and undressed, Ed.], 1374 pkgs butter, 20,508 carcases mutton, 315 carcases lamb, 2733 cases rabbits, 900 cases meats, 16 sacks grass seed, 1 bale horsehair, 213 pkgs sundries; total, 46,051 packages.

She loaded at Napier, Wellington, Lyttelton, Port Chalmers and the Bluff, and cargo was transhipped to her from Waitara. All the cargo shipped from Lyttelton was 632 cases of cheese.

The following are the particulars of the s.s. Mataura :— She was a steel screw steamship, gross registered tonnage 5764, under deck 5289 tons, net 3756 tons. Her class was 100 A1. She was built in April, 1896, by Barclay, Curle and Co., Limited, Glasgow. Her owners are the New Zealand Shipping Company, Limited. Her length over all is 421 ft, breadth 54ft 6in, depth 29ft 1in. Her port of registry is Plymouth. Her engines are triple expansion, with three cylinders, the diameters of which are 30in, 49in, and 78in respectively, length of stroke 54in. She is fitted with electric light throughout. She has capacity for 90,000 carcases of frozen meat. Her refrigerating machinery was of the "Linde ammonia" system, and was most efficient. The Mataura could attain a speed of 12½ knots. Altogether she was considered one of the finest of the Company's cargo boats, and in meat-carrying capacity equal to the Waimate and Rakaia. Her cost was between £70,000 and £80,000.

OFFICERS, CREW AND PASSENGERS.

The following is the list of the officers and crews:— Commander, C. A. Milward, R.N.R. ; chief officer, L. G. O. Silba ; second officer, E. G. Terry ; third officer, D. Maxwell ; fourth officer, E. C. F. Moore ; chief engineer, P. Sutherland ; second engineer, J. Thomas ; third engineer, J. B. Leech ; fourth engineer, W. R. Sneddon ; fifth engineer, J. Reed ; doctor, H. M. Page ; chief steward, F. Adcock; refrigerating engineer, J. W. Forrester; second refrigerating engineer, J. Scott ; electrician, Mr J. B. Leech ; chief steward, Mr F. Adcock ; chief cook, Mr John Howie ; boatswain, W. Green ; A.B.'s, J. Warty, J. J. Smith, G. E. Ball, M. McGensin, J. King, R. Smith, A. Culves, J. McGilligan, J. Batter, W. Cassidy, J. Brown, and F. Jeffries ; greasers, trimmers, firemen, &c, R. Johnston, P. O'Neill, D. Flanagan, F. Grant, J. Duncan, R. Armitage, E. Dowham, W. Mathie, M. Diamond, S. Pilbeam, T. G. Scotland, G. Petersen, F. Chappel, J. Willoughby, M. Graves, H. Martin, J. Dillon, J. A. Smith, W. Fraser, J. Cody, H. Giddes ; carpenter, J. Matheson ; stewards, pantrymen, cooks, &c., J. Wily, R. Jardine, E. Netherton, A. J. Thomas, W. Hemming, H. Redman, J. Donovan, J. Wolfe, G. Rennie, G. Andrew.

Mr Silba had command of the Company's ship Waipawa, and when she was sold was transferred to one of the Company's steamers, subsequently being appointed chief officer of the Mataura. Mr Leech is son of the Harbourmaster at Westport.

The passengers were Mrs A. J. Park and her daughter, Miss Katie Park, and Mr Thomas Mill. Mrs Park is a sister-in-law of Captain Milward and of Mr Barns, of Kinsey, Barns and Co. Mr Thomas Mill is a medical student, who was on his way Home to complete his course, and is a son of Mr John Mill, of Port Chalmers, who has held the contract for some years for the Company's stevedoring at Port Chalmers, Timaru and Oamaru.

The total number on board the Mataura, all told, was about sixty.

INSURANCES, &c.

A Press Association telegram from Wellington received last night says:—

It is estimated that the total value of the Mataura's cargo was some £300,000. There was £250,000 worth of wool, besides frozen meat, &c. All the companies doing business in Wellington hold risks on the cargo of the wrecked vessel. One company has a line of £33,000. The net loss of the Thames and Mersey Company will be £8000. The Commercial Union, China Traders, South British, Standard and Alliance are also understood to have heavy lines. The insurances on the vessel's hull are held in London.

A later telegram from the same place says:—

The hull of the Mataura was insured for £80,000 in the London Commercial. The Union Office has risks on the cargo to the extent of £30,000[?], the Canton Office £10,000, the New Zealand Insurance Company £33,000, but this latter is very largely reinsured. It is understood that £280,000 insurances on the cargo can be accounted for.

The Press Association agent at Dunedin telegraphs:— The National had lines to the extent of £20,000 on the cargo, reduced by reinsurances to £5000; the total insurance in the Standard Office was £16,000, largely reinsured. The South British at the Dunedin office had £8000 on the general cargo, reduced by reinsurance to £1500. Other insurances were — Victoria £6954, and British and Foreign £8000.

CAPTAIN MILLWARD.

A series of misfortunes (says a Press Association telegram from Wellington) has befallen Captain Millward [sic] during the last year or so, he having lost his wife and several members of his family by death. This had a detrimental effect upon his health, and he was unwell when last in Wellington. He has been connected with the Company for many years, having joined its service as third officer of one of the sailing ships, and he is regarded as a first-class seaman. At one time he was second officer of the Kaikoura, under Captain Crutchley. This is the first accident he has had since he went to sea.

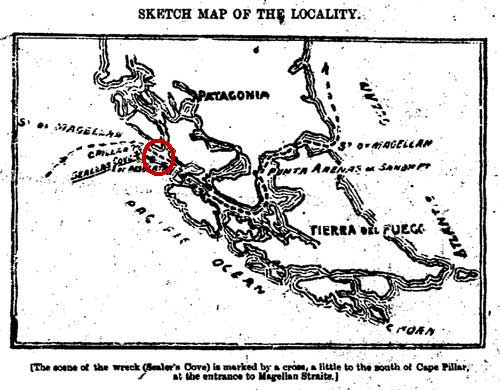

SCENE OF THE WRECK.

It will be seen from the sketch plan which we publish that Sealers' Cove, where the wreck occurred, is situated a little to the south of the entrance to Magellan Strait. Some of the passenger steamers belonging to the New Zealand Shipping Company, notably the Ruapehu and Ruahine, make a practice of going through the Strait. Cargo steamers usually go round the Horn instead, but we understand that the route is largely left to the discretion of the captain. Captain Millward, we believe, has been through the Strait, and is acquainted with its navigation. There is sometimes a difficulty in picking up the entrance in thick weather, but when Cape Pillar is passed the difficulties of navigation are not very great in the case of a steamer to a captain who knows the route. To a sailing vessel the strong current and west winds are a great hindrance. Magellan Strait, in fact, is now quite a busy highway for steamers, there being three or four lines running between the River Plate and Valparaiso. Our map shows the route through the Strait. The passage is 375 miles in length, and its breadth varies between twelve and seventeen miles. The western half is shut in by high, wooded mountains, with glaciers coming down to the water's edge, and the magnificent scenery has become a household word. Punta Arenas, or Sandy Point, where the survivors made their way in boats after the wreck, is about half-way through the Strait, and is now a port of some importance, having greatly grown since the introduction of sheep-raising into Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego. Steamers going through the Strait call there regularly.

It may be added that the natives of Tierra del Fuego are half-naked savages, very low in the scale of civilisation, and at one time they enjoyed a very bad reputation among sailors. In some of the older chart, they are marked down as cannibals. Missionaries have been at work among them and the frequent passage of steamers has helped to raise them a little in intelligence and civilisation. It is now one of the sights which passengers, look forward to to see them come alongside the steamer in their curious canoes and receive the little donations of tobacco and stores usually given to them by the captains of passing vessels.

Survivors return to Britain

Source: "Otago Daily Times", NZ, 5 April 1898

THE WRECK OF THE MATAURA.

ARRIVAL OF THE SURVIVORS IN LONDON.

TERRIBLE EXPERIENCES.

THRILLING NARRATIVES.

(From Our Own Correspondent.)

London, February 25.

Late on Wednesday night, the 23rd

February, the Pacific Steam Navigation Company's s.s. Orcana arrived in Liverpool, bringing with her three passengers and 59

of the crew of the New Zealand liner Mataura, lost at the entrance to Magellan

Strait. These 62 individuals were all on board the unfortunate vessel at the

time she struck, with the exception of her commander, who remained in the strait

to superintend salvage operations.

The night they arrived was bitterly cold, and the shipwrecked company looked forlorn and miserable, as they stood huddled together upon the Orcana's deck, many very scantily clothed, and others wearing garments which it was very evident had been made for someone else; for few had saved anything whatever from the wreck. The three passengers were Mr Thomas Mill (of Port Chalmers) and Mrs and Miss Park (also New Zealanders), and they seemed none the worse in health, though they lost all their belongings and suffered much from wet and cold in Magellan Strait. They were met by a representative of the New Zealand Shipping Company and their comforts seen to; while the crew were taken to the Sailors' Home, preparatory to being paid off in the morning.

I boarded the Orcana immediately upon her arrival, but found the Mataura's officers closely reticent as to the disaster and its causes. This is as usual, for, from sufficient reasons, a steamship officer is never communicative until after the verdict of the Board of Trade has been delivered. The passengers state that every care was taken to ensure their safety, and that they were kindly treated on board the Orcana, though they suffered considerable exposure in the strait. It was evident, however, that the passengers had been earnestly warned to tell practically nothing. I obtained the address of the two ladies and went to the hotel named, but either the address must have been purposely given incorrectly or else they. changed their minds and went somewhere else. At all events, it was impossible to find them in time for the outgoing mail.

Mr Mill, however, I did get hold of, and stuck to him most resolutely, never letting him out of my sight; but although he several times began a few rambling sentences he always broke off with "I would rather not," and there was generally an officer near to check him. When at last I got him started at the hotel one of the officers dragged him away almost by force, and he finally said, "These people have been good to me and they don't like it. I really will not tell you any more."

THE STORY OF THE DISASTER.

The crew, however, had much to tell, and the various stories may be summarised as follows:—

The Mataura was almost a new Clyde-built steamer, of first-class construction and material, and was then only on her third voyage. She left Wellington on the 21st December with what was, unfortunately for British underwriters, one of the largest cargoes on board ever shipped from New Zealand, including 30,000 carcases of frozen mutton and 1800 bales of wool. The voyage was, on the whole, uneventful until the night of the 26th of December, though some superstitious members of the crew aver that there were unlucky incidents from the beginning.

But on that night the engine condenser began to give trouble through failure of the air or circulating pumps. Such repairs as were possible at sea were made by the engineers, and for some days the Mataura proceeded on her voyage at a varying rate of speed, occasionally making as little as four knots an hour, until her commander was left to choose between two evils. He might try either to force a passage round the roaring Horn against the great ocean combers with a partially disabled steamer which could hardly be depended on to hold her own against the first wind which threatened to drive her ashore, or risk the passage of Magellan Strait. The latter alternative was almost as dangerous, for this mist-wrapped conglomeration of island and reef is swept by furious tides, against which the Mataura might really fail to make headway.

Eventually it was decided that the second course was the less hazardous of the two, and there being no other way, the Mataura was headed for Desolation Island, which is situated as the Western entrance of the strait. On the afternoon of the 9th of January she moved slowly toward the island, which loomed up faintly through drifting haze, crippled and steaming, so her crew aver, at considerably less than half speed, and at 2 o'clock struck violently and suddenly upon a submerged and uncharted rock near Cape Pillar some 12 miles from the mouth of the strait. Why, in these days of scientific survey and perfection of appliances, so many reefs and ledges should only be discovered by losing precious lives and valuable vessels upon them, hydrographers must be left to explain. Despairing underwriters grind their teeth and give the conundrum up.

After smashing and ripping half the bilge plates out of her, the Mataura slid off into deep water again, and the testimony about this is conflicting. Some declare that she bumped right over the reef in spite of her engines, and others that the swell swung her round sideways and drove her clear. Every possible revolution was got out of the screw, and she was headed directly for the land, firemen and engineers working in peril of their lives to keep her engines going, so that the helmsman above should at least have steerage way. Their efforts, however, were in vain, and they barely escaped death by scalding when within an hour of the time she struck the sea poured into her red hot furnaces. Then a roaring mass of steam and cinders swept aloft from funnel and grating, and the Mataura was left with useless engines and fires drowned out, sinking rapidly in a confused roll of tide-stirred sea. The grimy staff below had done their part, and it now remained for sailorman and deck officer to make the best of a hopeless case; and they apparently did it well. Every available stitch of canvas was set, and the vessel, lurching more heavily at every wallow, drove slowly toward the threatening line of crag and reef before her. There was no sheltered opening to be seen in all the iron-bound coast ahead, and if there had been it is hardly probable she could have steered toward it, for the total sail area of a large modern steamer is rarely sufficient to hold the vessel against a moderate tide, and tides are not moderate in Magellan Strait. So passengers and crew waited and wondered whether she would sink beneath them in deep water or go to pieces on the inhospitable coast, until at last she struck again close in to the land. Her forepart was wedged fast upon a jagged ledge, while her stern settled down into the depths beyond.

Here she hung, grinding and pounding heavily, with a long steep sea lapping her sides, and it was as well she was not crowded with passengers, for the work of lowering the boats was arduous. Discipline and skill, however, prevailed, and the task was accomplished at last — how hard it is to get boats safely away from a wreck under these circumstances only those who have seen it done can comprehend. In the end every soul on board was taken off, and it became a question where the boats might land. To attempt to get ashore upon shark's-tooth ledges swept by roaring surf was, of course, impossible, and it was only after long and weary labour at the oars that an inlet known as Sealers' Cove was reached. There the shipwrecked company came thankfully ashore, wet and cold, most of them bringing nothing with them but what they stood up in, while to make matters worse there was very little to eat. They passed the night shivering and hungry, and on the morrow a daring and successful attempt was made to board all that remained of the Mataura — a part of her forward length — in search of provisions. Afterward the officers took counsel together, and decided that, as they could not stay on that inhospitable rock and starve on the odd chance of being picked up, the only course was to make for the little Chilian [sic] station of Punta Arenas (Sandy Point), toward the other end of the strait.

The boats were launched again, and a new difficulty remained to be faced. There was a confused tumbling mass of white-topped sea between them and the comparative shelter of the strait beyond Cape Pillar, and the voyagers in the different craft met with varying fortune. One boat was driven back half full as many as four times, while the remaining three seemed to have been able to force their way toward smoother water more quickly. Wind and sea were both dead against them, and it was a tough battle, in which the craft pulling most oars with the strongest men behind them came off the best. The first to arrive at Punta Arenas was the captain's, and the others came in one by one at intervals — some being four days on the way, and the longest seven.

It was a very memorable voyage, and men who had been shipwrecked before say it was one of the hardest experiences they ever went through. It was bitterly cold most of the time; a pitiless drizzle, alternating with heavy showers, oozed down, soaking them to the skin, and when this ceased for a scanty interval clammy mist took its place, which was almost worse than the rain. Part of the while a nipping wind blew fair through the straighter of the channels, and with lugsails set the boats made good way; but this failed in the winding passages, and the oars were thrown into the crutches again. Magellan Strait is a nest of reefs and kelp beds, swept by swirling tide eddies, which in the races sometimes pile themselves up on end, and through these dangerous waters the weary, rain-soaked men grimly fought their way. It is a testimony to the skill of those in command, and the strength and endurance of the men at the oars that they reached Punta Arenas at all. Here the party were, on the whole, well received, and shortly afterward the Orcana steamed into sight and took them off. The Mataura's captain remained behind to negotiate with a Chilian company for salving as much of the cargo as might be reached, and it was understood would have to pay 75 per cent on what was saved. This is another tremendous loss for underwriters to face, and the latter have already sufficient reason to hate the very name of Magellan Strait, where it is not long since another fine vessel was lost, going down in 10 minutes after she struck. Passengers and crew all bore it philosophically. It was hard luck, but might have been very much worse, but for the prudence of those in command they said, and they were very thankful to have saved their lives.

A SAILOR'S THRILLING NARRATIVE.

This is the plain tale of one of the crew, told amid the approving nods of his companions, and, corroborated by letters sent on from Lisbon to the friends of others at Home:—

"If an officer talks he generally gets the sack," he said, "but our contract ends each voyage, and we're paid off from the very day the ship comes to grief. We were steaming toward Cape Pillar when it happened, going very slow, with crippled engines, and seeing nothing clearly, and she brought up on an uncharted rock. I don't know if they could have cleared it if it had been charted. That's for others to say. And you can't do much with the engines out of gear. She hit the ledge, hard and stopped there a bit, the rivets smashing somewhere underneath, and the plates grinding and ripping — you could hear them go at every bump. Then she was off again; wallowing, the water gurgling under decks, and her head turned toward the land. They all did their best below, but it wasn't any good; she sunk lower all the time; and you could tell by the drowsiness of the lift and the kind of drunk way she pitched her head she wouldn't be long on top. Next the fires went; I don't know how they kept way on her so long, and we half expected someone would be scalded to death. It was about an hour, I should say, before the stokehold was drowned. We got all the sail on her we could, but you could see by the way the water crawled past she was doing very little under canvas. Still she blew in all the time towards the land, and the land looked lots worse than the reef — all steep rocks and ledges, with white spouts of surf and spray; but it was either that or Davy Jones in open water, and small chance of the boats.

"Officers and skipper were smart men," he continued, "and they kept her steering for the best of it; and that was bad enough, until she hit a ledge again and stopped there, for good and all this time. Then came the work, and I've seen many a boat smashed over an easier job than this. But there were good men in charge, and all hands took it cool and quiet. Besides the davit-blocks and falls weren't stiffened up with paint and rust like you see them on many a ship, where you can't get a boat over the side without a marlin spike and hatchet to begin."

Here the narrator seemed disposed to wander off into a dissertation on the ways of previous vessels he had sailed in, and one of the rest took up the tale:— "We got them all off at last," he said, "and the two ladies in, though some of the boats were a bit smashed banging against the ship's side, and then it looked as if every bone was to be broken trying to get ashore. The officers were wise, and they made for a place called Sealers' Cove, where we managed to make a landing, and a miserable place it is. A miserable lot we were, too — all soaked and worried; with very little to eat, and only one or two of them got their clothes. I got mine, though — always keep them handy, for I've been in a sudden affair before, and I don't like Magellan Strait. I slept, starving and wet, and next morning we goes off again to the poor Mataura. She lay with her head cocked up and her stern under, a-grinding still, and the deck like a roof. But we got on board, for it was either that or starving, and when you've done that kind of thing before you don't want to try it again.

"We was driven back four times struggling to get round Cape Pillar, the boat half-full, and flung all ways at once, and the men wet to the skin and blue all through with cold. Then we fetches the strait, where it's sheltered from the Pacific roll, and we got a slant of wind. We set the lug, and run her away for Punta Arenas, and saw nothing much of the rest. No, we hadn't the luck to sail long, either — you can't expect a fair wind to follow you round every corner, — and then we met the tides. Round some points they run, ail breaking white, and you may guess what it's like taking a boat through that. But there wasn't a soul who grumbled, and they done their best with the oars. I seen two men who couldn't hardly loose their hand from the loom when the wind came fair again. Sleeping in an open boat in pools of water, wet to the skin, when you've been pulling the inside out of you all day, isn't any joke either; but we done it, and the officer helped us all he could. I don't think it stopped raining two hours at a time, and when it did there was fog and cold winds that went through you to the bone. In some of the passages it blows like mad, and then you come round a corner into a calm, where the rain comes down in sheets, and you can't see anything for banks of haze. None of us know just how we won through, for half the time there was no marks to steer by, and when the tide was going the right way it just swirled us along, sometimes into thick darkness, the water piled up on end all about, and the boat going round like a top in the strongest flow. It's a ghastly country any way — all islands like chopped off mountains thrown down into the sea, and on some of them not a goat could land, and we didn't want to try. When the tides ran hard against us we looked for an eddy, and let go an anchor in the slackest bit we could find, and then went on whenever we could make head against the stream.

"At last we fetched Sandy Point — five days I think it was, and that many days too long. They were not so bad to us there, but no one was sorry when the Orcana came along and took us off. Treated all right in her; you generally are in a decent ship, for the Government sends you home; and wages to draw tomorrow from the day she struck."

The tender's whistle had hurried the narrative to a conclusion, and the last of the Mataura's men followed the passengers on board the tug, where many stood shivering beneath the awnings with very little between them and the cold. Mr Mill was attired just as he was when he got up the day the Mataura struck, for the passengers, expecting to feel the steamer go down beneath them every moment, were too anxious to save their lives to think of searching for warmer clothing and something to protect them from the weather.

Magellan Strait has long been regarded as one of the most dangerous waterways in the world, abounding with sharp turns and reefs swept by currents of tremendous force, and shrouded almost continuously, in snowstorm, mist, or drizzle. At the western, or Pacific end, where the Mataura came to grief, it seems as though the Andes had been broken up into detached masses and thrown down into a waste of breaking surf. The islands are generally bare masses of lava and scoria, destitute of food or shelter, and only few fish-eating Indians, eke out a miserable existence about their shores. The latter, it is said, are addicted to the piracy of stranded vessels and the plunder of shipwrecked seamen when they get the chance. Therefore, everything being considered, the passengers and crew of the Mataura may be congratulated on escaping as well as they did, and if there is any sympathy to spare the unfortunate underwriters who insured her probably deserve it most.

Board of Trade Enquiry, London: First Hearing

Source: "Press", Canterbury, NZ, 11 June 1898

LOSS OF THE S.S. MATAURA.

NAUTICAL ENQUIRY.

ALLEGED BREAKDOWN OF MACHINERY.

(from our own correspondent.)

LONDON, May 7.

A further chapter relating to the loss of the s.s. Mataura in the Magellan

Strait, on January 12th last, was opened in the Guildhall, Westminster, the

day before yesterday, when a Court of Enquiry, ordered by the Board of Trade,

commenced an investigation. The Court consisted of Mr Marsham, Magistrate,

and Captain Parfitt and Mr Ronaldson, Assessors. Captain Milward was present,

and all parties interested were represented by counsel. Mr Israel Davis and

Mr Bullock appeared for the owners of the ship (the New Zealand Shipping

Company), and Mr Nelson, solicitor, for the master, Captain Charles Amherst

Milward. The Board of Trade presented a series of questions dealing with

material events connected with the casualty, &c.

Captain Milward, late commander of the Mataura, was the first witness called upon to give evidence. He was under rigid examination for over three hours, in fact more, for after being in the box the whole of the morning, he was re-called after the luncheon adjournment at the request of Captain Parfitt, who subjected him to a keen questioning to show that the bearing Captain Milward said he took, and the course he thereon steered, would have placed the ship right on the Apostles Rocks in the Strait. The witness, however, was able to demonstrate that it would have taken him six to seven cable lengths away, or the best part of a mile. The main points of Captain Milward's testimony were that on December 26th there had been a breakdown of some portions of the machinery; that there had been temporary repairs, followed a few days later by a further stoppage of the engines; that he did not care to go outside the Apostles for fear of running further risks; and that in taking the inside passage he had struck a submerged rock. He detailed the after experiences, but they have already been dealt with by me in a previous letter. I may mention, however, that the Captain added that just before the striking the weather was thick with rain.

Mr Terry, the second officer of the Mataura, who was the officer on watch at the time of the vessel striking, gave some additional particulars. Both the captain and the chief officer were on the bridge when the vessel struck. He went on duty at noon, and twenty minutes later saw rocks on the port bow. These he reported to the captain, who ordered the helm to be put hard a-starboard; the rocks were then about six miles and a half off. The weather was overcast. They kept the Judge's rocks in sight on the starboard side, and there was a second alteration in the course. This was about 1.50 p.m. at 2.5 p.m. the ship struck twice. The rocks on which she struck could not be seen; there was one about six cables' length away that could be seen.

What do you think caused the casualty?

The ship striking on the rock. (Laughter).

Mr Leech, the Mataura's third engineer, said that on December 26th the pumps became disabled in consequence of one of the links giving way. They proceeded without the pumps the rest of that evening and night, but on the following day they stopped and made an attempt to repair the damage. Then they started once again to steam, but on the next Sunday they stopped to make a proper job of it; this they did by making a new link. This would be on Sunday, January 2nd, or Monday, January 3rd, and they did not stop afterward till the vessel struck. However, a very sharp look-out was kept in the engine-room; in fact, an extra man was put on there on account of the breakdown. They did not repair the feed pumps. Asked as to whether the link that had broken had ever broken down before, witness replied that he believed it had on the previous voyage, when it had been repaired at Capetown. Witness could not say whether the engines had been surveyed when the ship returned to London.

Mr Sneddon, fourth engineer, remembered the pump breaking down. At the first repairing they "shackled" the chain; at the second repairs they still had the shackles on. After that the engines worked well, but they stopped a third time to put in a new "distance piece" of wood for the shackle. The vessel struck so hard that it made him stagger. The first blow was forward, the second farther aft. Immediately after the blow he heard the chief engineer tell a man to go and shut the tunnel door; the chief also went himself. Witness, too, went to lend a hand when the place was half full of water. He did not know what had become of the ratchet used to close the door. They could not close the tunnel door. The reason for this was, he thought, that the vessel had struck right underneath the bulkhead. It might have been that the door frame was fractured, but he could not say that this was so. He never saw anyone try to open or shut the door before when he was on watch.

William Green, boatswain, having narrated the orders he had received as to getting out the starboard anchor, to attending to the sails, and launching the boat.

Carpenter Mathieson said after the vessel struck he sounded the wells. In the No. 4, that was the engine-room, he found 3½ft of water; he sounded two other wells, and found from 5ft to 6ft of water. He reported to the captain that the ship was going down. Witness saw them try to shut the tunnel door, and failed. He did not know what had become of the ratchet, and spanner used to close the door, but there were several that could be used.

It was here intimated that the Superintendent Engineer of the Company, who had made a survey before the vessel left, could give evidence if that was desired.

Mr Marsham said that the Court did not desire it.

For the Board of Trade it was stated that if the Court wished questions relating to the tunnel door and the alleged break-down of machinery embodied with those previously framed, it would be necessary to adjourn.

Mr Marsham—How long before the chief engineer and chief officer are available? We understood the captain to say that the engines were in such a state that he could not trust them, and that, therefore, he went inside the rocks. That seems to be the line of defence; therefore, it appears very important that we should hear the chief engineer.

Objection was here raised to such a long delay as this would involve. The vessel in which the chief engineer and chief officer of the Mataura had again sailed for New Zealand, had only left England about three weeks, and she was not timed to leave the colony on her return voyage until June 9th. What was to "become of the poor captain meanwhile?"

Mr Marsham—Up to that time I do not see why he should not pursue his calling, only he must not go a long way off.

This, it was strongly urged, would be impossible. Captain Milward had been with the Company for seventeen and a half years, and they only traded to New Zealand. Beside, he had already been kept a long while from employment as it was.

Mr Marsham—I should be sorry to keep him from his employment, but the state of the engines appears to me to be the crucial point. Practically, the captain says —"I did not dare to go outside. Although I knew it was risky, I had to go inside.'

Finally, after discussion with the assessors, Mr Marsham said—"I don't think we can arrive at a satisfactory conclusion without the chief engineer and the chief officer."

The enquiry was then adjourned sine die, the Board of Trade authorities undertaking to continue Captain Milward's detention allowance in the interim.

Board of Trade Enquiry, London: Second Hearing

Source: "Otago Witness", NZ, 15 September 1898

THE LOSS OF THE MATAURA.

EXONERATION OF THE CAPTAIN.

(From Our Own Correspondent.)

LONDON, July 30.

At the Town Hall, Westminster, yesterday the Board of Trade inquiry into the

loss of the New Zealand Shipping Company's s.s Mataura in the Magellan Strait

on January 12 last, was resumed before Mr Marsham, magistrate, and Captain

Parfitt and Mr Ronaldson, assessors. Mr Israel Davis was for the Board of

Trade, Mr Laing for the owners of the ship, and Mr Nelson for Captain Milward,

who was in command at the time of the casualty.

It will be remembered that the inquiry opened on the 6th May last, when Captain Milward, Mr Terry (second officer), and Mr Leech (third engineer) gave evidence. Captain Milward having stated that owing to recent breaks-down in the machinery he dared not go outside the strait, the inquiry was adjourned for the presence of the Mataura's chief engineer and chief officer, both held to be material witnesses.

At the resumed inquiry yesterday the first witness was Mr Paton Sutherland, who had been chief engineer of the Mataura. He described the breaks-down in the machinery. After the links of the pump had carried away the second time he condemned the lot, and made some new ones. He cut up fire tubes and boiler tubes, and made a couple of new sets. These new ones proved satisfactory. They ran well, but of course they could hear them. Once or twice he had to tighten the lattice chains, and had rigged round it. He tried to get the whole thing as rigid as possible. He supposed he pulled the engines up on this occasion for a few minutes. After repairing the links he increased the revolutions regularly, and had no anxiety as to whether he would get to England. The engines were running about 50.8, or about 9 knots. On. the day the vessel struck they were raising steam in the third boiler; they had only been working two till then. When they made land on January 12 the captain and he congratulated themselves with the work she was doing. At that time he remarked that before they got down to the dangerous parts of the strait it would be as well if they stopped and had a general look round, and then "belt" her through. The captain said he wanted to make some soundings for the Hydrographic department in London, and would do so when they stopped the engines. After striking, the water came into the engine room from the fore side of the tunnel door and from under the thrust. He left the fourth engineer, Sneddon, on the bottom platform, and got away on the top platform and proceeded to close the tunnel door. In this he had the assistance of two or three of the engine-room hands. They closed the door with a spanner, but not with the proper spanner for the door, which had never been in his department; it was kept in the ship's department. He had seen the carpenter on a previous voyage close the door with the proper spanner. So far as he knew they succeeded in closing the door. The thrust recess was full, so that they could not tell whether they had closed the door. He believed the men succeeded in closing the engine-room door, but he would not swear it. It took three men instead of one to give the six or eight turns to the spanner, which he considered necessary to shut the door.

By Mr Laing: He was aware of the company's instructions that the water-tight doors should be regularly closed and tight. That practice had been carried out on both the last two voyages.

By Mr Nelson: He had repeatedly asked the chief officer for the proper spanner, and had made a bucket by the door, so that it should be always in its place. He did not tell the captain immediately after the wreck that the door would not close, and that the spanner was lost. The engines had broken down on the trip previously, but not so seriously as on this voyage.

By Mr Israel Davis: He understood the captain to say that he would stop when he got round Cape Pillar.

Mi Leonard George Silba, who had been chief officer of the Mataura, was next examined.

Mr Israel Davis, then, on behalf of the Board of Trade, handed in the following questions for the consideration of the court:— (1) What number of compasses had the vessel; were they in good order and sufficient for the safe navigation of the vessel; and when, and by whom, were they last adjusted? (2) Did the master ascertain the deviation of his compasses by observations; were the errors correctly ascertained, and proper corrections to the courses applied? (3) Whether, on the afternoon of the 12th January last, it was necessary for the master to navigate the vessel outside of the outer rocks of the Apostles Rocks, and, if not, was he justified in attempting the passage? (4) Whether a proper look-out was kept? (5) Where the vessel struck, and is the rock marked on the Admiralty chart? (5A) Was the water-tight door in the bulkhead immediately aft the engine-room closed immediately after the vessel struck, and, if not, why not? (6) Whether the vessel was navigated with proper and seamanlike care? (7) Whether the loss of the Mataura was caused by the wrongful act or default of the master?

Captain Milward was then recalled by the court. He was, he said, going to take soundings outside the Strait of Magellan. He had taken soundings on the previous voyage for the Hydrographic department, and he wished to correct these. They were marked on his chart.

Cross-examined by Mr Marsham: Captain Milward said he would have to take five or six soundings, perhaps a dozen. Of course the ship would not stop to take soundings. He had a special sounding-machine. He was going to rely exclusively on that, and was not going to stop the ship at all. His reason for going inside was that he thought the engineer wanted to stop the engines. It had nothing to do with the soundings. Undoubtedly it would save one and a-half or two hours. That was not the reason he wanted to go inside. It had nothing at all to do with it, and the soundings formed a different matter altogether. He took soundings going along in the morning, and this time he was not on the same track on which he took the old ones. It would be no use. He did not intend to take any more. When he found himself off the land, he discovered he was seven miles to the southward of his old soundings, which he attributed partly to making more leeway than he allowed for, and partly to more current than he allowed for. The currents were decidedly uncertain on that coast.

Captain Parfitt then said that there was a rock marked about half a mile from the mainland.

Captain Milward replied that he saw breakers there, but he did not go near them.

Mr Nelson then handed in the following translation from Spanish of two divers who had examined the wreck: "Have examined the bottom of the wrecked steamer. There is a hole from 20ft to 24ft long by l½ft wide (more or less) in the bottom, from the mainmast towards aft. A little further aft there are some bulges, but no holes. The bottom, from the mainmast to the bows, shows no damage whatever. After the steamer ran aground in the entrance to Sealers' Cove she broke in two, her fore part becoming submerged from her bridge to bow."

This had been duly certified before notaries.

Mr Nelson, for the captain, in his address, said that the lee way may be accounted for by the fact that the engines were not working efficiently from December 27 to January 4. But apart from the engines, when land was picked up it was manifestly the captain's duty to taper off the land. It must be considered, too, that the wind, sea, and current were against him, and that the weather was hazy. With regard to the differences in the evidence of the captain and the chief engineer, whatever the exact terms of conversation were, the impression on the captain's mind was that the engineer wanted to stop the engines. They had already been stopped twice, and the only reason the captain could have had for taking the vessel inside was the impression left by the engineer. There was a fair wind to carry them round the Horn, but the chief engineer had stated that the captain had told him that he must stop the engines; the chief officer added that it was impossible to do better than was proposed. What was the prudent course for the master to do? Clearly, to shorten his distance and get into smooth water where the engines could be stopped and seen to as speedily as possible. Therefore he determined to take the vessel between the North Apostle and Cape Pillar. On the chart there was no indication of the rock on which the vessel struck; that it was a submerged rock was proved by the divers' report. And he thought that had the bulkhead door been closed aft, the vessel might have had a different fate. Mr Nelson handed in records of the satisfactory career of the captain from the time he joined H.M.S. Conway, through his service with the New Zealand Shipping Company. He also read a letter from that company stating that Captain Milward had always proved a well qualified officer, of sobriety and great attention to duty. In accordance with the rule of the company, Mr Nelson added that he could never, however, be employed by them again.

Mr Israel Davis pointed out that lines in the chart showed the place not fully charted, and therefore it behoved every sailor to be doubly careful while the sailing directions stated that in the vicinity of the casualty there was considerable broken water from submerged reefs. The captain knew very well that he should not have gone in the vicinity of these except in case of the greatest emergency. The captain, after the striking, managed the vessel in a seamanlike manner. He thought the court might express an opinion that, as navigation in these parts was constantly increasing, steps should be taken to obtain greater certainty as to charting. But people in charge of valuable ships and valuable lives must not take these risks as if they were in little yachts.

The court, after an hour's deliberation, gave its finding. This, after answering formal questions as to the compasses, etc., stated that the instruments were correctly adjusted and proper courses applied. On the afternoon of January 12 it was not necessary for the master to navigate the vessel inside the outer rock of the Apostle Rocks; considering that the master was seven miles south of his expected position, that the weather had cleared, that the engines had been disabled on two occasions after having been repaired, and that the master had reason to suppose that they were still in an unsatisfactory condition, the court was of opinion that he was justified in attempting the passage. From the evidence, a vessel drawing 24ft of water struck about half a mile to the S.E. of the North Apostle Rock; on this position there was nothing marked on the Admiralty chart; but the Admiralty sailing directions stated that near the Judge and Apostles' Rocks there were many breakers, indicating extensive reefs. The watertight bulkhead aft the engine room door was probably not closed after the striking, though every attempt seemed to have been made to close it, but the court did not attribute it not being closed to the fact that the proper spanner was not used. The vessel, they found, was navigated with proper and seamanlike care, and the master was not in default.

Captain Milward's certificate was then handed back to him.

Cleared of blame [but still lost his job]

Source: "Evening Post", Wellington, NZ, 3 August 1898

The Board of Trade enquiry into the wreck of the New Zealand Shipping Company's steamer Mataura, which was lost in the Strait of Magellan, South America, in January last, has resulted in the master being exonerated from blame.