Anglican Missionary Endeavour in Tierra del Fuego (1832-1916)

Historical Review

Background

Increased British influence around the globe after the Napoleonic Wars (1815 onward) was accompanied by growing social concern for the welfare and Christian "salvation" of all mankind, regardless of racial group or prevailing religious faith. The Victorian era was a veritable "golden age" of missionary endeavour, at times in the vanguard of formal colonisation, at others quite independent of it. For instance, public support for abolition of the Negro slave-trade led British Christian missionaries to both west and east Africa (the Scottish doctor-explorer David Livingstone being one well-publicised example).

The First Experiment

The earliest recorded British attempt to convert

the indigenous peoples of Tierra del Fuego was organised by Captain Robert

Fitzroy of the Royal Navy.

The earliest recorded British attempt to convert

the indigenous peoples of Tierra del Fuego was organised by Captain Robert

Fitzroy of the Royal Navy.

In the course of the hydrographic survey of the Beagle Channel in 1830, he had induced four young natives ("named" York Minster, Boat Memory, Jemmy Button, and Fuegia Basket) to accompany him to England. Fitzroy was a man of strong religious convictions. At his personal initiative and expense, the natives were placed under the care of Rev. William Wilson (a member of the Church Missionary Society) taught the English language, dressed according to the British custom and trained in "civilised" behaviour.

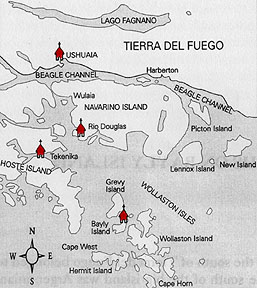

Fitzroy returned to these southern waters in 1833, accompanied by York, Jemmy and Fuegia (Boat had died early on). On January 27th, these three were installed in a simple hut at Wulaia (on Navarino Island), with the catechist Richard Matthews, in the expectation that they would educate the local groups in enlightened ways. This well-meaning attempt lasted a mere 10 days: Matthews was severely harassed and had to be withdrawn.

Early Missionary Societies

Encouraged by the glowing report of Captain Benjamin Morrell, the Boston-based American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions authorized an exploratory visit to the Pacific coast of Western Patagonia. In late 1833, two recently-ordained missionaries were landed in Eastern Patagonia (San Gregorio). They found it impossible to cross to the Pacific (by land or by sea), instead using their two-month stay to make valuable contacts with the local Tehuelche (Aónikenk) peoples. The Board's final decision, however, was that local circumstances were not propitious for founding a mission station.

Retired Navy Captain Allen

Francis Gardiner was a moving force behind the growth of Anglican missionary

society work in the region. During 1844/45 (with the support of the Brighton

Missionary Association for Patagonia) he and Robert Hunt attempted

to establish a mission among

the Tehuelche and Yamana peoples at San Gregorio, on the north shore of

the Strait of Magellan (where sovereignty had recently been asserted by the

Chilean government). Their letters to home provide

a glimpse of the dangers and practical difficulties of their situation. This

mission was abandoned.

Retired Navy Captain Allen

Francis Gardiner was a moving force behind the growth of Anglican missionary

society work in the region. During 1844/45 (with the support of the Brighton

Missionary Association for Patagonia) he and Robert Hunt attempted

to establish a mission among

the Tehuelche and Yamana peoples at San Gregorio, on the north shore of

the Strait of Magellan (where sovereignty had recently been asserted by the

Chilean government). Their letters to home provide

a glimpse of the dangers and practical difficulties of their situation. This

mission was abandoned.

In March 1848, Gardiner made an unsuccessful attempt at settling on Picton Island (at the eastern approach to the Beagle Channel). Then, in December 1850, he and six companions returned to Picton and established camp; they were driven out and took refuge at Puerto Español, a secluded inlet on the north shore of the Channel. Sadly, all died of starvation before the expected relief vessel arrived.

Local Base of Operations

Once word of the tragedy reached Britain, there was a rush of sympathy for this type of undertaking. With the increased financial support, the Patagonian Missionary Society (PMS) purchased a vessel, renamed the "Allen Gardiner", which was dispatched in 1855 to Keppel Island, in the Falklands [Malvinas]. The new strategy, in the interests of safety, was to persuade small groups of natives to visit Keppel for short periods of time. The first attempts failed; but by 1858 the way seemed clear to establish another "beach-head", once again at Wulaia, on the west coast of Navarino Island. However, tragedy struck in November 1859, when five members of the group were killed, only the ship's cook being spared.

Explorations Northward

The missionary work at Keppel did not cease, only paused. After exploring the pampas lying to the north of the Magellan Strait in 1858-59, Theophilus Schmid tried fruitlessly to negotiate a mission site on Elizabeth Island (near Punta Arenas) to serve as base of operations for work among the Tehuelche tribes of the mainland. Together with Hunziker, he built a hut at Weddell's Bluff, near the mouth of the Santa Cruz River (on the Atlantic seaboard); however, relations with the local natives were difficult and unproductive, and the project failed. [see footnote]

The Ushuaia Mission

Despite these repeated setbacks, the PMS superintendent, Rev. Waite Hockin Stirling, was determined that the Society's work should proceed, and in 1863 he went to meet the Yamanas in person; in 1865 the society was renamed the South American Missionary Society (SAMS). The acculturation of natives by visits to Keppel Island continued. In 1867, a small settlement was established at Laiwaia (or Leuaia, on Navarino Island, near the Murray Channel), occupied by four trained Yamanas. This advance-post was a success.

By 1869, Stirling was ready to found a fresh missionary station. A house was erected at Peninsula MacClinton, near present-day Ushuaia, and he moved in alone, accompanied only by a few trusted Yamanas. Little by little, the new community prospered, and by the end of six months a small group of natives were practising the rudiments of vegetable and livestock farming, learning to erect buildings and being instructed in the Christian way of life. Stirling's faith and courage were rewarded: the settlement had taken root.

Rev. Thomas Bridges

In 1871 a new superintendent

arrived in Ushuaia:

Rev. Thomas Bridges

and his young family. Bridges had come to Keppel as a child in 1856 with

his adoptive father Rev. George Despard, and had thoroughly assimilated

the native culture and language.

His work at Ushuaia was correspondingly enlightened,

and successful. In 1873 Bridges was joined by

John Lawrence,

another dedicated missionary, who likewise raised a family there.

In 1871 a new superintendent

arrived in Ushuaia:

Rev. Thomas Bridges

and his young family. Bridges had come to Keppel as a child in 1856 with

his adoptive father Rev. George Despard, and had thoroughly assimilated

the native culture and language.

His work at Ushuaia was correspondingly enlightened,

and successful. In 1873 Bridges was joined by

John Lawrence,

another dedicated missionary, who likewise raised a family there.

Years of strenuous endeavour followed, but the outside world was drawing ever closer. The Argentine government had begun to take an interest in the administration and development of this remote area, and a military garrison was established nearby. Increased contact with visiting ships repeatedly brought infectious diseases, which were frequently fatal to the indigenous people. The use of alcohol as an item of trade was another blow, as it led to personal dissipation, social disintegration and even murder.

Believing that his work could not continue in these changed conditions, Bridges resigned from SAMS in 1887 and moved further east, to Harberton, an isolated spot where he and his family developed a ranch. About 60 Yamanas were employed as farm workers, thus continuing in lay fashion the civilising work begun at Ushuaia.

The Bayly Mission

Meanwhile, in 1888, Aspinall had negotiated with the Chilean government the right to establish a new mission station in the Wollaston Islands, a little north of Cape Horn. Before year's end, Leonard and Nellie Burleigh, with their young child, were transferred from Keppel and settled on Bayly Island. The natives of this area lived in poor conditions, and the adverse weather made the couple's task arduous in the extreme. Helpers were sent from Ushuaia, and the mission´s orphanage at Ushuaia was transferred there also. Not until 1892, however, was it possible to transfer the mission to a more sheltered site, at Tekenika Bay, on Hoste Island.

The Tekenika Mission

This third mission had an inauspicious start. Almost 200 natives had congregated around the site, but it was too late in the season to plant food beds and the animals had not arrived. With supplies arriving occasionally by boat, and the natives away foraging, all construction work fell upon the two male missionaries. Almost everyone succumbed to illness, and conditions were very stressful. Then in late 1893, Burleigh was drowned and the project was in crisis, relying on a series of temporary missionaries until Peter Pringle and his wife arrived to maintain continuity of the work.

The Rev. John Williams (who had worked briefly at Tekenika in 1895) and his family returned to Tekenika in 1902 after a six-year term as chaplain of the new Anglican church in Punta Arenas. In the intervening years, a dedicated team of missionaries had expanded the mission buildings, providing all the help they could muster. But the Yamanas were a dying race, and the mission was too remote. The end was inevitable, and in 1907 the missionaries transferred their base of operations for the last time.

The Río Douglas Mission

The new mission, at Río Douglas, was located on Navarino Island, further north than its two predecessors, where communications to Ushuaia and Punta Arenas were easier. Williams and his wife were dedicated workers, extending the buildings, and caring for the remaining natives' bodies and souls. The "flock" was not going to be abandoned, but the extinction of the race was well under way. The Keppel mission closed its doors in 1911, and last of all Río Douglas, in 1916. The Williams's returned to the booming city of Punta Arenas, where they continued to labour among the "new Patagonians" for the remainder of their days.

The Salesian Missions

With the advance of regional development, and the tensions provoked by territorial disputes, it was inevitable that the Anglican presence (however well-intentioned) should arouse political and religious uneasiness among the Argentine and Chilean authorities. This would explain, for example, Schmid's inability to secure the use of Elizabeth Island.

Starting three decades later, missionary work on the continental mainland and the "big island" of Tierra del Fuego was performed instead by the Roman Catholic Salesian congregation. Originating in Italy, this group of priests and nuns worked predominantly with the Ona peoples of the interior of the "big island", who later came under intolerable pressure from the sheep ranchers. They are still prominent to this day in education and community work among the general population.

Conclusion

Historians have drawn contrasting conclusions from this episode in the region's history, which was, in essence, a classic "frontier" phenomenon. From a pragmatic point of view, the Anglican missions were a failure: the native race could not be adequately shielded from the encroaching white settlers, and was extinguished within a few generations; its cultural heritage exists nowadays only in books and photographs.

Taking the religious perspective, however, leads to a more positive interpretation: the culture shock was attenuated by the presence of sympathetic mediators; adjustment to the new reality allowed a few of the natives to integrate economically and genetically with the dominant group; and an example of selfless humanitarian behaviour ("Christian charity") was held up to the public gaze, both locally and in far-away Britain. There seems to be a conundrum -- is there ever such a thing as a "lost cause"?

| Bibliography

(English and Spanish) -- compiled by Denis Chevallay |

|| | Missionaries and catechists | || | Map of Tierra del Fuego |

| || | Photographs from Tekenika | || | The four mission stations |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||