The British Presence

in Southern Patagonia

+ + Historical Summary + +

First Contacts

|

From the perspective of far-away Europe, the southern tip of America was long seen as inhospitable and worthless [the title of a recent book by a Scottish author sums this up rather nicely — "Why Patagonia?"]. Spanish attempts in the 16th century to colonize the Magellan Strait (discovered in 1520) were unsuccessful. From then onward, the region called Patagonia was first and foremost an obstacle on the long sea route to Spain's colonies of the Pacific: its importance lay exclusively in the strategic southern sea passage. For more than two centuries after its discovery, the best known British to come this way were adventurers, such as Drake and Cavendish, looking for spoils in Spain's distant dominions. |

Sea passage from Europe to the Pacific |

Exploration and Expansion

Grave marker, San Julián, Lt. Sholl, HMS Beagle, died 20-I-1828 |

The growth of the British Navy gradually brought a more serious purpose. Research voyages were undertaken to different parts of the world. The explorations of Cook helped to fill in many blank spots on the globe, and paved the way for later mass emigration to Australia and New Zealand. When the Spanish colonies of South America revolted in the early 19th century, Britain seized the geopolitical opportunity, and provided material and technical assistance to several of the new republics. To support its role as a global naval power, the British government subsequently sent hydrographic surveys to map the Patagonian coasts, including the innumerable fjords and channels of the west and south. The best known of these voyages were commanded by Fitzroy in the "Beagle": incidentally, on one occasion, he brought back local tribesfolk to Britain where they were treated as a public curiosity. |

Gradual Development

|

The new republics of Chile and Argentina gradually established physical sovereignty over the southern outposts of their territory, but economic development was a long way in the future. Meanwhile, in Britain, evangelism was in the air, and a succession of missionaries tried to convert the Yahgan canoe people to Christian ways. In 1869, George Musters explored the interior of the landmass, still home to the nomadic Ona and Tehuelche peoples. In 1879, the small port town of Punta Arenas (founded in 1848) was rebuilding from the ashes of a prison revolt 2 years before. Not until 1885 did Río Gallegos appear on the scene. |

Tehuelche girls |

Immigration and Industrialization

Estancia Gente Grande, Tierra del Fuego, sorting wool, 1943 |

To sum it up in a single word, what changed everything was "sheep". Sheep-raising reached its "eastern limit" in Patagonia after 1833, when the British took possession of the nearby Falkland Islands (Malvinas). Sheep ranching was profitable in the islands, but offered few economic opportunities for the individual farmer. From the late 1870's onward, some settlers from the Falklands moved on to Santa Cruz and Magallanes, attracted by state grants and privileges. There they acquired, and worked on, large expanses of land called "stations" (estancias). Soon, an export industry was created for wool and meat, following the pattern already developed in New Zealand. The scale of operations rose to industrial levels: a single large frigorífico (freezing works), could process as many as 250,000 animals in a season. Britain's role in this rapid development was many-fold: investment capital, industrial and husbandry expertise, and a large export market. By the early 1900's, there were several thousand Brits living in the region, drawn by the opportunities of this new source of wealth. |

Diversification and Decline

|

The star which brought the Brits to these shores has faded. Although sheep ranching is a visibly important activity in the region today, world events, political trends, new technologies and natural disasters have all taken their toll. Other economic activities (such as oil production and tourism) have overtaken the estancia (ranch) and the ovejero (shepherd). Few British live here nowadays: but there are still numbers of local families, on the land, in the professions or in business, which can trace their roots back to those "gringos" of earlier times. |

![Frigorífico Bories ["the end of the line"] rails](../../img/rr/bories-rails.jpg)

Frigorífico Bories ["the end of the line"] |

Enduring Reminders

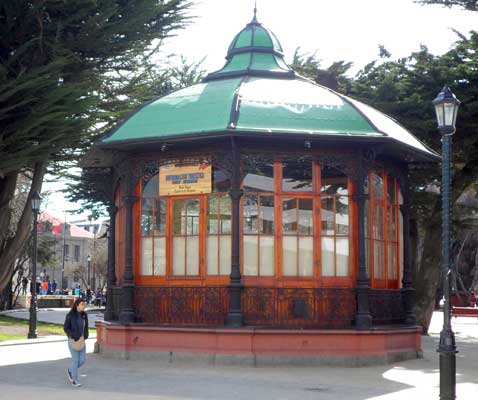

Bandstand, Main Square, Punta Arenas |

At first glance, the modern visitor to Patagonia might conclude that the British in Southern Patagonia have disappeared without leaving any trace of their presence and former importance. Scratching the surface, however, yields surprises. To take an example — the main square in Punta Arenas, the region's first economic powerhouse. Directly in front of the Government building stands a tall flagpole, focal point of public events and ceremonies: a plaque records that it was donated to the city by the local British community in 1943. Meanwhile, in another part of the plaza, there is an attractive Victorian-style bandstand, circa 1910: the manufacturer's mark shows that it was built in Kirkintilloch, Scotland. |